Building the Ultimate Carbon Capture Tree

Building the Ultimate Carbon Capture Tree

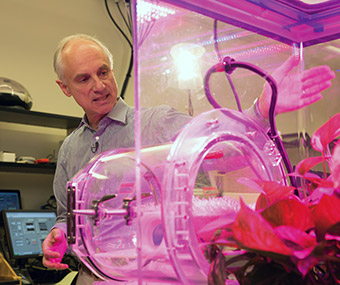

Lackner's artificial tree with the array of carbon-capturing material that folds up accordion-style when full. Image: Jessica Hochreiter, Arizona State University

This story was updated on 2/3/2023.

On Arizona State University’s campus sits an artificial tree—instead of leaves and branches, though, you’ll see a metal column and 5-foot diameter disks silently pulling carbon dioxide out of the air. But the carbon dioxide doesn’t get turned into fruit, roots, or tree trunks, as it does with a natural tree. Instead, it simply gets collected by resin in a reversible chemical process.

This “tree” makes up for in efficiency what it lacks in aesthetics. According to Klaus Lackner, founder and director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State, it’s currently more of a process than an actual product—but it can extract carbon dioxide 1,000 times faster than a natural tree.

Read ASME’s Top Story: Air Taxi Aces Test Flight

One machine, though, won’t be enough. Considering the 36 gigatons emitted by humans every year, it will take another, and another, and maybe 100 million units—each the size of a shipping container—to extract a ton of carbon dioxide from the air each day. At that scale, a forest of artificial trees could potentially keep up with the current carbon emission rate.

One hundred million is a large number, Lackner admitted, while also noting that we are capable of building 80 million cars and trucks each year. For millions of those machines to be built, it’s crucial that the cost is low and the performance is high.

According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, all the living matter in all the plants on Earth—from the grass in suburban lawns to the rainforests of the Amazon—equals around 150 billion tons.

Another 300 billion tons are locked into non-biologically active trunks and stems. Since around 1900, however, the fraction of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased from 280 parts per million (ppm) to about 412 ppm. The mass of the carbon in that added CO2 is 280 billion tons, far more than plants could lock up over any reasonable time scale.

If humanity is going to draw down the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to avoid the worst effects of climate change, as scientists recommend, it will require something other than plants. An industrial-scale problem calls for industrial-scale solutions.

“Once the carbon is in the atmosphere, we have fewer solutions for removing it,” said Matt Lucas, managing director of business development at New Energy Risk. “Direct air capture is one of those solutions.”

At the source

Klaus Lackner started his career as a theoretical physicist, eventually landing at Los Alamos National Laboratory in the mid-1980s. Over time he was drawn to the practical challenges of carbon capture. By the late 1990s, Lackner realized not only that human economic activity was going to rely on fossil fuels for decades to come, but also that we’re unable to capture roughly half of the CO2 we put out because nearly half the emissions are coming from non-point sources.

Much of the focus of carbon capture has been on point sources, such as power plants and cement factories, where industrial processes create a concentrated stream of carbon dioxide. Capturing CO2 from point sources is like pulling water from a hose.

“It's almost certainly cheaper to capture carbon emissions from their source—or never emit them in the first place,” Lucas said.

Register today for ASME’s Offshore Wind Summit

Even if capture could be deployed at all point sources, it would simply slow the rate of emissions. If we are going to reduce the atmospheric CO2 concentration, we can either wait hundreds of years for nature to do it, or we can begin to actively withdraw it from the air.

Take a journey through Pratt & Whitney’s North Berwick, Maine, plant: Manufacturing Takes Flight

Unlike point sources, where CO2 concentrations in exhaust streams are relatively high, capturing CO2 from the atmosphere—where it makes up roughly one part per 2,500—is more challenging. This problem is neatly summarized in what’s called Sherwood’s Rule: the cost of extraction scales linearly with the degree of dilution. Combined with the already high cost of flue-gas scrubbing, that suggests that the cost of direct air capture of CO2 would be prohibitive. Any attempt to economically capture CO2 directly from the air must find a way around Sherwood’s rule.

A few companies have rolled out air-capture demonstration projects—Carbon Engineering in British Columbia, Climeworks in Switzerland, and New York City-based Global Thermostat, for example—all of which use blowers or fans to drive air through their capture systems. Though that helps speed the reactions, it’s also energy intensive. And if that energy comes from fossil-fueled power plants, then the whole process threatens to be counterproductive.

Looking for a way to use less energy in the initial collection stage, Lackner came across a Japanese project that collected uranium from seawater using artificial kelp. Uranium concentration in seawater is only three parts per billion, more than 100,000 times more dilute than atmospheric carbon dioxide. This suggested a way around Sherwood’s rule: relying on passive collection.

By avoiding any processing until the carbon dioxide has been substantially concentrated, the energy required to remove the CO2 should be reduced dramatically. Finding a medium that can cycle between capturing and releasing the gas without applying heat or pressure would reduce the energy requirements even more.

Capture the gas

Conventional carbon dioxide sorbents absorb the gas when cool and release it when heated, which creates the necessity for a constant energy supply. Lackner’s team found an inexpensive material that operates on a different cycle: it absorbs CO2 when dry and releases it when wet.

According to post-doctoral research associate Shahrzad Badvipour, the sorbent consists of anionic exchange resins, where the resin will bind CO2 as a bicarbonate ion when in a dry state. “When wet, a carbonate ion forms,” explained Badvipour, “replacing two bicarbonate ions resulting in the release of a single molecule of CO2.”

A prototype carbon capture system running in Lackner’s lab consists of rigid rectangular channels made of sorbent-impregnated polypropylene, roughly an inch wide and a quarter-inch tall. As air passes through, the material picks off the molecules of carbon dioxide. When saturated, the filter is dunked in water and placed in a terrarium. A gas analyzer tracks the concentration of CO2 in the terrarium, which rises as the wet filter releases the absorbed carbon dioxide, then drops as the gas is taken up by a potted geranium.

Once the filter is dry, it is removed from the terrarium and the cycle starts again.

Adapting this process into a forest of artificial trees has been challenging, though. Some of the first renderings depicted enormous tuning fork-shaped structures jutting out of the landscape or panels that would fold accordion-style into a vat of water.

Read ASME’s Long-form story on Robots: Robots to the Rescue

An additional design involves disks of sorbent loosely stacked into cylinders to allow air to flow over each surface. At regular intervals—roughly every 1,000 seconds—the stack collapses into a canister that then seals itself up and sprays water over the disks, releasing the absorbed gas. Lackner’s team envisions a cluster of 16 of these stacks, with one collapsing and one springing up each minute.

To collect the CO2 from the stacks that are outgassing, a vacuum would be pulled continuously, using a clever ejector system based on the Bernoulli effect, through a system of valves that switch its input to whatever cylinder is being harvested at the moment. The concept is similar to the system used in steam railroads to draw cold water into pressurized boilers. The flow is directed such that the output of the most depleted cylinder feeds into its neighbor that immediately preceded it in the sequence, which in turn feeds into the one that preceded it. The net effect is that the last cylinder to close is “topped off,” at which point its CO2 is harvested.

The lab also has developed a concept that employs a sorbent fabric belt in a continuous loop, with half the loop exposed to the open air collecting CO2 and the other half in an air-tight container where it is wetted to release the gas.

These designs have been sized to produce a CO2 concentration of five percent—roughly 125 times higher than what is found in ambient air. That’s rich enough to allow further concentration through conventional means.

Optimize and deploy

For decades, Lackner’s vision of artificial trees pulling CO2 from the ambient air seemed closer to a hallucination than a practical engineering project. But that changed fast with the presence of Robert Page, a project manager with a background in product development.

Page was brought in to help shepherd the artificial tree technology from the laboratory to mass production. One of the first decisions was which concept to build on. In many ways, the closed-loop system seemed to offer some advantages in scalability. In the near term, however, the team decided to go ahead with the stacked-disk system. Though it would require some sophisticated controls to approximate a continuous output from what is essentially a series of batch processes, it was judged to be simpler, less expensive, easier to manufacture, and easier to transport and set up.

Producing a system that operates along the lines of a natural system, while elegant in conception, does involve certain compromises—particularly with regard to maintaining a constant stream of gas, as most production systems would be expected to do. Another challenge is where to site those 100 million shipping container-size devices. Given the sorbent cycle’s dependence on drying, deserts seem ideal, but many windy areas also would be suitable.

The key, however, is to pull carbon dioxide out of the air as quickly as possible. Lackner’s artificial trees will never be as elegant as an aspen or as majestic as a sequoia, but if they can help limit the damage from too much CO2 in the atmosphere, they will be beautiful enough.

R.P. Siegel is a technology writer based in Rochester, N.Y.