NASA Mines the Possibilities

NASA Mines the Possibilities

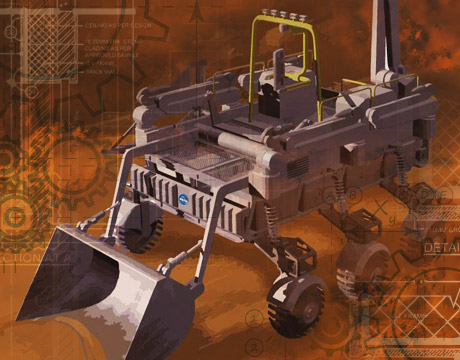

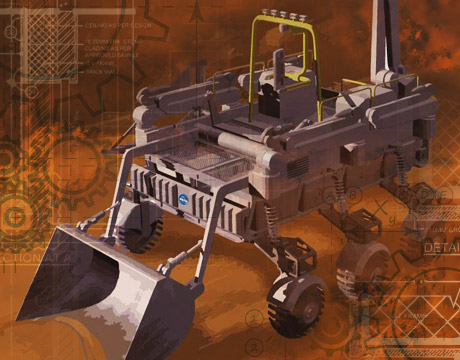

Rover image: NASA

NASA is simultaneously encouraging collegiate achievement and looking for innovative breakthroughs as the organization considers the future exploration of Mars. At least that is what Brent Chester, logistics leader for the University of Alabama’s team in NASA’s Robotic Mining Competition thinks. His team recently won the competition for the third consecutive time, and, now a senior, Chester has been a part of the competition for four years.

“NASA is out to test items going into space and the goal with the competition is to begin [moving your robot] from a starting zone and you have to navigate to other side of the pit for digging,” he says. “You pick [the payload] up and come back and deposit it, but just as important as all this digging is keeping the weight down on the robot. Autonomy is what we specialize in. We’re the only team to do at least one run autonomously and this year we did two. It’s a great chance to get used to how industry is: high expectations and answering to others in a project setting where results will be decided.”

In reality, the competition is a year-long process of preparation but it culminates with approximately 50 universities competing in a “showdown” each May at the Kennedy Space Center, he explains.

The actual mining is the most visual aspect of the quest to determine a winner. But other factors include a 20-page systems engineering paper about all research, design, planning, and building of the robot; a five-page essay on outreach; and a slide presentation category, in which teams give a two-minute presentation to NASA judges, he says.

Mechanically, Chester’s team, known as Alabama Astrobotics, revised this year’s model to have a separate door mechanism and they added a bigger head to allow for more control in digging depth. This robot they consider to be their eighth iteration and their fourth year in a row using a bucket design. “There are a bunch of buckets on it. The purpose of the bucket design is it’s the most efficient way to dig up as many materials as you want.”

Chester finds the competition helps him take classroom knowledge and utilize it in the real world. Working your way up the ranks and receiving more responsibility is a part of the university team as well, and Chester recalls receiving a good deal of help learning about cutting materials and mill work as he made his way up.

Rising to the rank of logistics leader, he’s had a chance to learn more of the business aspect of the field recently, from budgeting to collecting money, and now has the goal of receiving an MBA. He is slated to graduate with his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in August.

“I like to be able to understand what engineers present and understand how to package that and how to talk about it.” From talking to potential clients and sponsors and presenting, he believes he’s found his own niche in engineering.

In that sense, the competition is only just beginning.

Eric Butterman is an independent writer.

We’re the only team to do at least one run autonomously and this year we did two.Brent Chester, Alabama Astrorobotics