Sensor-Packed Glove Helps Surgical Students Learn

Sensor-Packed Glove Helps Surgical Students Learn

Glove records surgeon’s movements and monitors those of students.

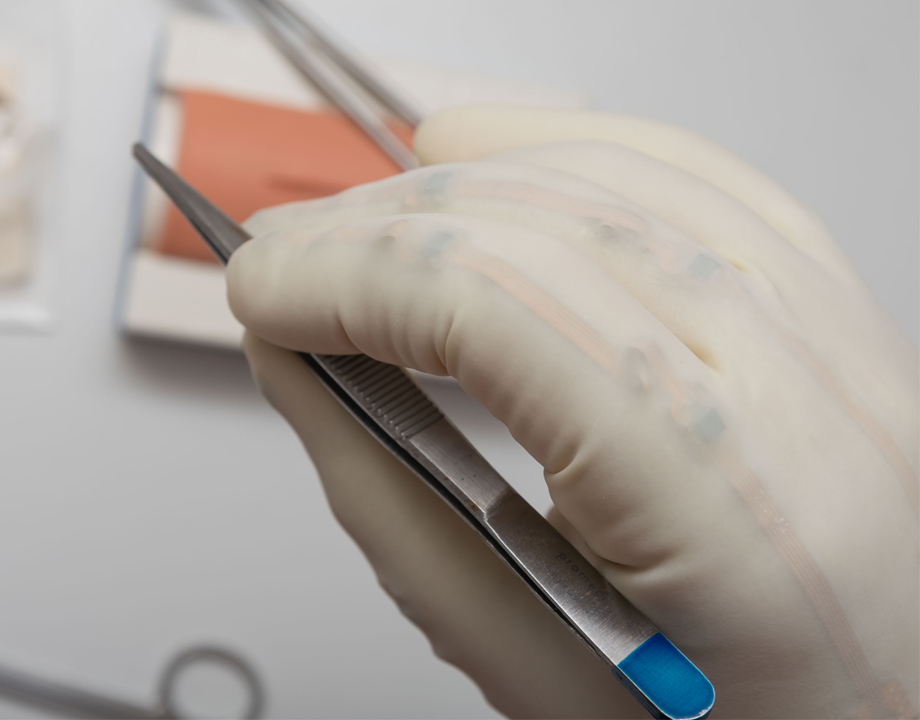

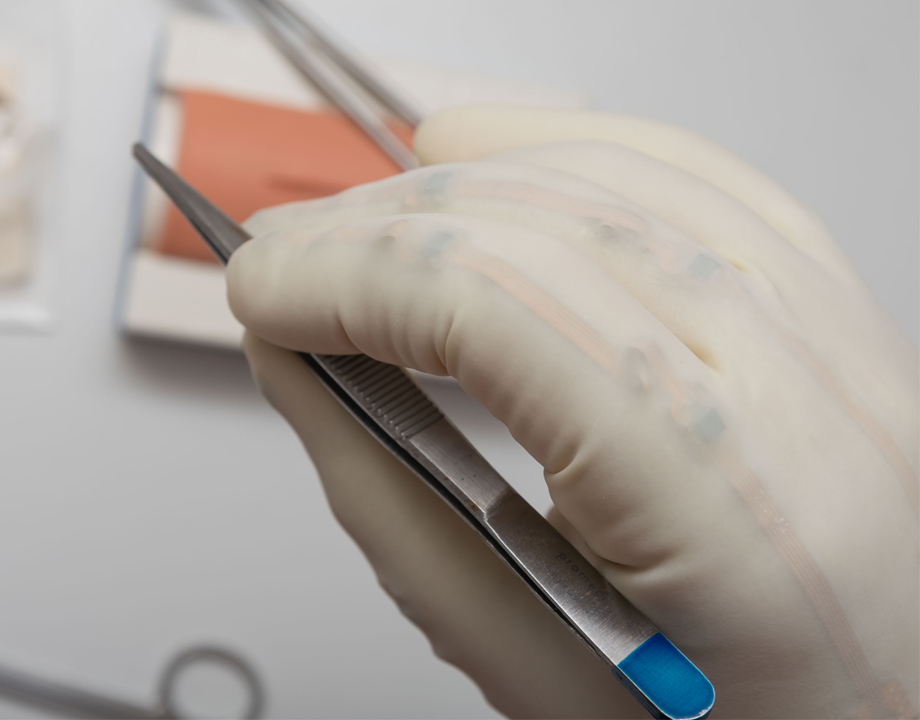

Surgical knots and sutures are made with precise, well-learned movements that have been committed to muscle memory by experienced executors. The current method of teaching these digital manipulations is to have seasoned surgeons watch surgical students at practice and make comments.

This pedagogical technique is less than ideal. For one thing, different surgeons can offer different advice, which can be frustrating for the student. Experienced surgeons also cannot always be around to monitor a student’s every practice stitch. The best of them have limited time and can only impart their expertise to a limited few. Further, patients and instructors alike would like to minimize practice performed in situ in the operating room.

“Surgery, as a discipline, is seen as quite difficult to master,” said Gough Lui, a biomedical engineer at Western Sydney University’s MARCS Institute for Brain, Behavior and Development. “And a lot of surgeons are getting to the age where they are considering retirement. They fear that their skills would perhaps vanish if not handed down. We could make those skills last a little bit longer than the person.”

To do that, Lui has created a new tool for handing down those skills: a surgical glove outfitted with sensors. The glove can both record the movements of master surgeons and monitor those of the learner. By comparing the latter against the former, students can fine tune their performance.

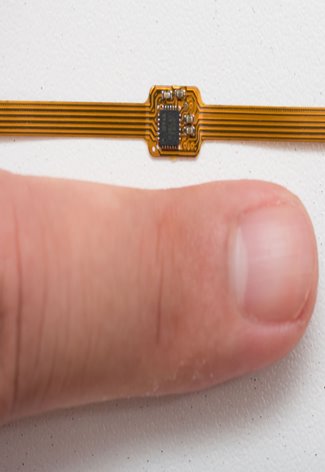

Lui’s first protype was outfitted with accelerometers on the back of the glove and force sensors in the fingertips. But he soon found that surgeons don’t like to feel anything on their hands, especially at the sensitive ends of their fingers. So the current training glove uses IMUs—the inertial measurement units found in smart phones—that can record high-resolution data at a high rate, and can be encapsulated in silicone without hampering their performance. As a result, the gloves can record acceleration and rotation as well as sense a finger’s “jerk index” of how quickly it’s moving, and the direction in which it is pointing.

The development of the glove is, arguably, one of the easier aspects to the project. More time consuming is collecting the data from surgeons and turning it into something useful. Lui and his team are still in the process of building a library of sutures from seasoned surgeons. They do have many volunteers.

Listen to the Podcast: A Catheter Small Enough to Treat Brain Aneurysms

“We do have quite a few surgeons keen to get their hands on the device and provide the data,” Lui said. He also hopes to eventually gamify the system, allowing students to check—on a phone—their actions against those in the library.

But that doesn’t mean that students will be able to learn without a senior surgeon around. “We can’t cut the human out of the loop,” said Lui. “What we’ve seen is that students really need that human feedback. It might be a psychological or emotional need.”

But when no mentor is around, the glove could be useful stand in: Practicing without any feedback at all can reinforce poor technique. Still, the gloves won’t provide anything like tactile feedback to fingers or hand, as studies have shown the skills of students trained with haptic feedback regress once that feedback is removed.

More for You: Soft Robotic Glove Boosts Workers' Grip

Once perfected, the glove may have uses beyond training students. For instance, after the surgery slowdown brought on by COVID-19, there’s been a measurable decline of confidence among surgeons. The glove could offer them an easy way to get back up to speed. Similarly, active surgeons could use it to get ready for an operation.

“Sometimes they get nerves before a surgery, they need something to warm up, like a vocal singer,” Lui said.

Surgery isn’t the only vocation that requires highly practiced hands. Musicians from within the institute have inquired about using the glove to observe and measure percussionists.

But before anyone uses the gloves to learn how to execute a paradiddle on their tom-tom, or a friction knot in the emergency room, there’s work to be done. The data from surgeons has to grow, and it has to be analyzed. Lui hopes to have a working protype, with a large and usable library, by the end of the year.

“The hope is that by doing this we will be creating better surgeons and better health outcomes,” he said.

Mark Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.

This pedagogical technique is less than ideal. For one thing, different surgeons can offer different advice, which can be frustrating for the student. Experienced surgeons also cannot always be around to monitor a student’s every practice stitch. The best of them have limited time and can only impart their expertise to a limited few. Further, patients and instructors alike would like to minimize practice performed in situ in the operating room.

“Surgery, as a discipline, is seen as quite difficult to master,” said Gough Lui, a biomedical engineer at Western Sydney University’s MARCS Institute for Brain, Behavior and Development. “And a lot of surgeons are getting to the age where they are considering retirement. They fear that their skills would perhaps vanish if not handed down. We could make those skills last a little bit longer than the person.”

To do that, Lui has created a new tool for handing down those skills: a surgical glove outfitted with sensors. The glove can both record the movements of master surgeons and monitor those of the learner. By comparing the latter against the former, students can fine tune their performance.

Lui’s first protype was outfitted with accelerometers on the back of the glove and force sensors in the fingertips. But he soon found that surgeons don’t like to feel anything on their hands, especially at the sensitive ends of their fingers. So the current training glove uses IMUs—the inertial measurement units found in smart phones—that can record high-resolution data at a high rate, and can be encapsulated in silicone without hampering their performance. As a result, the gloves can record acceleration and rotation as well as sense a finger’s “jerk index” of how quickly it’s moving, and the direction in which it is pointing.

The development of the glove is, arguably, one of the easier aspects to the project. More time consuming is collecting the data from surgeons and turning it into something useful. Lui and his team are still in the process of building a library of sutures from seasoned surgeons. They do have many volunteers.

Listen to the Podcast: A Catheter Small Enough to Treat Brain Aneurysms

“We do have quite a few surgeons keen to get their hands on the device and provide the data,” Lui said. He also hopes to eventually gamify the system, allowing students to check—on a phone—their actions against those in the library.

But that doesn’t mean that students will be able to learn without a senior surgeon around. “We can’t cut the human out of the loop,” said Lui. “What we’ve seen is that students really need that human feedback. It might be a psychological or emotional need.”

But when no mentor is around, the glove could be useful stand in: Practicing without any feedback at all can reinforce poor technique. Still, the gloves won’t provide anything like tactile feedback to fingers or hand, as studies have shown the skills of students trained with haptic feedback regress once that feedback is removed.

More for You: Soft Robotic Glove Boosts Workers' Grip

Once perfected, the glove may have uses beyond training students. For instance, after the surgery slowdown brought on by COVID-19, there’s been a measurable decline of confidence among surgeons. The glove could offer them an easy way to get back up to speed. Similarly, active surgeons could use it to get ready for an operation.

“Sometimes they get nerves before a surgery, they need something to warm up, like a vocal singer,” Lui said.

Surgery isn’t the only vocation that requires highly practiced hands. Musicians from within the institute have inquired about using the glove to observe and measure percussionists.

But before anyone uses the gloves to learn how to execute a paradiddle on their tom-tom, or a friction knot in the emergency room, there’s work to be done. The data from surgeons has to grow, and it has to be analyzed. Lui hopes to have a working protype, with a large and usable library, by the end of the year.

“The hope is that by doing this we will be creating better surgeons and better health outcomes,” he said.

Mark Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.