Evinrude Outboard Motors Changed Summer Forever

Evinrude Outboard Motors Changed Summer Forever

An ASME engineering landmark, Ole Evinrude's small marine engine was an instant success in the early 20th century.

On small lakes across the United States, summer is synonymous with the sound of small outboard motors. These machines power fishing boats and pleasure craft that enable families and friends to spend time on the water. Without them, boats would be able to go only as far as their owners could row.

ASME recognizes engineering landmarks based on their innovation and impact, and as far back as 1981 the Society bestowed this honor on a pioneering outboard motor and the entrepreneurs who made it famous.

Ole Evinrude was an immigrant from Norway whose family settled in central Wisconsin in the 1880s. Much like neighboring Minnesota, Wisconsin is a land of small lakes that attract fishermen all year round. Ironically, however, Evinrude showed little interest in rural life in his early years. As a teenager, he moved to Madison to become an apprentice in a farm machinery shop and later found work in Pittsburgh and Chicago. Eventually, he settled in Milwaukee and co-founded a company to make a standardized, drop-in replacement motor for the earliest automobiles.

According to a story told by Evinrude, he was picnicking with his fiancé on an island on a hot summer day when she told him she wanted some ice cream. Evinrude rowed his boat 2.5 miles to the mainland to fetch the treat. On the return leg, Evinrude realized that the sorts of gasoline-powered engines he was building for land vehicles might serve an important role on boats.

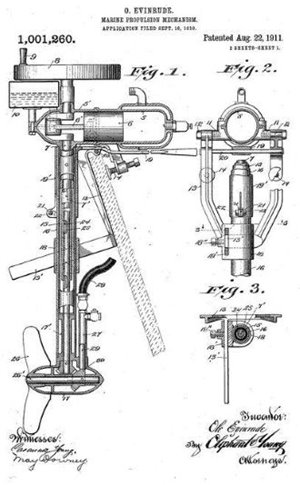

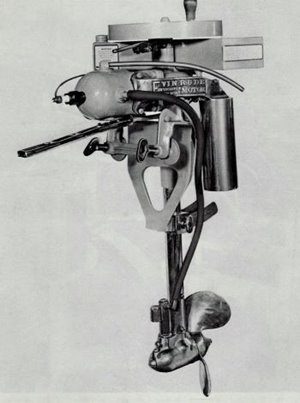

A year later, Evinrude and his now-wife, Bess, unveiled an outboard motor. The invention placed a gasoline engine at the top, connected via a long shaft to a submerged propeller. The 62-pound two-cycle internal combustion motor ran at 1 1/2 horsepower at 1,000 revolutions per minute. The cylinder was horizontal, the crankshaft vertical, and the direction gears housed in a submerged unit. The design has remained standard for outboard motors.

Bess said it looked like a coffee grinder.

The first generation of Evinrude motors was designed by Ole, while Bess handled the business side and marketing. According to one account, Bess wrote the advertising copy, “Don’t row. Throw your oars away. Use an Evinrude motor.”

The itch to innovate was hard for Ole Evinrude to ignore, and by 1921 the Evinrudes founded a new company to compete against Evinrude Motor Co. The new outboard motor Ole had designed was a marked improvement over the original. Built from aluminum, it used two cylinders instead of one, weighed 47 pounds—half the weight of his first outboard—and produced 3 horsepower instead of 1.5 hp.

His innovation spurred competitors to develop improvements on their own products, and within a decade such inventions as full pivot steering, slip-clutch propellers, and an auxiliary gas tank were commercialized. Evinrude’s company even branched out to land, marketing lawn equipment under the Lawn-Boy brand.

Between the competition among rival companies and the economic impact of the Great Depression, the stress of keeping the business afloat was intense. By 1934, both Bess and Ole had died, and the business was taken over by their son, Ralph. In spite of the loss of its founders, the business thrived, acquiring and consolidating rivals in the manner that General Motors had. Evinrude and its various brands under the umbrella Outboard Marine Corporation became synonymous with outdoor recreation.

According to Bill Ziehm, a retired associate engineering project lead at OMC’s corporate research center, “Ralph was always hands on.” Even in the 1970s, when Ziehm started working at OMC, Ralph Evinrude would round up the new engines every year, put them on boats, and try them out firsthand.

Ziehm describes OMC as a conglomerate with a wide breadth of interests. For instance, it was the fourth largest maker of electric vehicles at one time, due to its line of electric golf carts. “We were on the leading edge in a lot of fields,” Ziehm said.

At the time of the designation of the ASME engineering landmark in 1981, the company had annual sales of $700 million—$2.5 billion in today’s dollars. A plaque announcing the designation was set up next to a display of one of the first Evinrude motors in the headquarters of Outboard Marine in Milwaukee. But the company soon started losing money on a regular basis.

According to Ziehm, one of the main problems with OMC’s outboard motor business was that two-stroke engines fell out of favor. “We lost the perception battle with people,” Ziehm said. “The two-stroke engines we had were very clean, but we were never able to convey that knowledge to the public.”

After several attempts at reimagining the business, Outboard Marine went bankrupt and its outboard motor divisions were purchased by the Canadian firm, Bombardier. In 2020, the Evinrude brand was discontinued after more than 110 years.

“I put my whole life into it, so it’s tough to see it gone,” Ziehm said.

Even so, the impact that Ole Evinrude had on the small engine business and outdoor recreation is immeasurable. After his landmark outboard motor, summer would never be the same.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

ASME recognizes engineering landmarks based on their innovation and impact, and as far back as 1981 the Society bestowed this honor on a pioneering outboard motor and the entrepreneurs who made it famous.

Ole Evinrude was an immigrant from Norway whose family settled in central Wisconsin in the 1880s. Much like neighboring Minnesota, Wisconsin is a land of small lakes that attract fishermen all year round. Ironically, however, Evinrude showed little interest in rural life in his early years. As a teenager, he moved to Madison to become an apprentice in a farm machinery shop and later found work in Pittsburgh and Chicago. Eventually, he settled in Milwaukee and co-founded a company to make a standardized, drop-in replacement motor for the earliest automobiles.

According to a story told by Evinrude, he was picnicking with his fiancé on an island on a hot summer day when she told him she wanted some ice cream. Evinrude rowed his boat 2.5 miles to the mainland to fetch the treat. On the return leg, Evinrude realized that the sorts of gasoline-powered engines he was building for land vehicles might serve an important role on boats.

A year later, Evinrude and his now-wife, Bess, unveiled an outboard motor. The invention placed a gasoline engine at the top, connected via a long shaft to a submerged propeller. The 62-pound two-cycle internal combustion motor ran at 1 1/2 horsepower at 1,000 revolutions per minute. The cylinder was horizontal, the crankshaft vertical, and the direction gears housed in a submerged unit. The design has remained standard for outboard motors.

Bess said it looked like a coffee grinder.

The first generation of Evinrude motors was designed by Ole, while Bess handled the business side and marketing. According to one account, Bess wrote the advertising copy, “Don’t row. Throw your oars away. Use an Evinrude motor.”

Instant success

The motors found almost instant success. In fact, an account by former president Theodore Roosevelt of his expedition up the Amazon River praised the reliability and durability of his boat’s Evinrude outboard. Sales were strong, but the stress of running a rapidly growing business took its toll. The Evinrudes sold the company in 1914 and retired.The itch to innovate was hard for Ole Evinrude to ignore, and by 1921 the Evinrudes founded a new company to compete against Evinrude Motor Co. The new outboard motor Ole had designed was a marked improvement over the original. Built from aluminum, it used two cylinders instead of one, weighed 47 pounds—half the weight of his first outboard—and produced 3 horsepower instead of 1.5 hp.

His innovation spurred competitors to develop improvements on their own products, and within a decade such inventions as full pivot steering, slip-clutch propellers, and an auxiliary gas tank were commercialized. Evinrude’s company even branched out to land, marketing lawn equipment under the Lawn-Boy brand.

Between the competition among rival companies and the economic impact of the Great Depression, the stress of keeping the business afloat was intense. By 1934, both Bess and Ole had died, and the business was taken over by their son, Ralph. In spite of the loss of its founders, the business thrived, acquiring and consolidating rivals in the manner that General Motors had. Evinrude and its various brands under the umbrella Outboard Marine Corporation became synonymous with outdoor recreation.

According to Bill Ziehm, a retired associate engineering project lead at OMC’s corporate research center, “Ralph was always hands on.” Even in the 1970s, when Ziehm started working at OMC, Ralph Evinrude would round up the new engines every year, put them on boats, and try them out firsthand.

Ziehm describes OMC as a conglomerate with a wide breadth of interests. For instance, it was the fourth largest maker of electric vehicles at one time, due to its line of electric golf carts. “We were on the leading edge in a lot of fields,” Ziehm said.

At the time of the designation of the ASME engineering landmark in 1981, the company had annual sales of $700 million—$2.5 billion in today’s dollars. A plaque announcing the designation was set up next to a display of one of the first Evinrude motors in the headquarters of Outboard Marine in Milwaukee. But the company soon started losing money on a regular basis.

According to Ziehm, one of the main problems with OMC’s outboard motor business was that two-stroke engines fell out of favor. “We lost the perception battle with people,” Ziehm said. “The two-stroke engines we had were very clean, but we were never able to convey that knowledge to the public.”

After several attempts at reimagining the business, Outboard Marine went bankrupt and its outboard motor divisions were purchased by the Canadian firm, Bombardier. In 2020, the Evinrude brand was discontinued after more than 110 years.

“I put my whole life into it, so it’s tough to see it gone,” Ziehm said.

Even so, the impact that Ole Evinrude had on the small engine business and outdoor recreation is immeasurable. After his landmark outboard motor, summer would never be the same.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.