Ethics in Engineering

Ethics in Engineering

Engineers need to consider the ethical implications of the products they create. Some of them may surprise you.

You may think the field of engineering doesn’t lend itself to philosophical questioning. The truth is, engineers and philosophers alike need to ponder the ethical implications of new technologies like artificial intelligence and 3D printing.

The need for ethical reasoning is greater than ever, said James Mickens, who co-directs of the Embedded EthiCS program at Harvard University. For example, autonomous cars free humans from driving, but may pose new risks to drivers and pedestrians. Facial recognition systems speed lines but can discriminate against certain populations.

Today’s computer scientists must learn to design systems that are morally and socially responsible, said Alison Simmons, a Harvard philosophy professor. Engineers are no different.

More for You: Workforce Blog: Opening Doors to Opportunity

Computer science majors at Harvard now study ethics through Embedded EthiCS modules. The program teaches students how to think through the ethical implications of their work, she said. Simmons also co-directs program.

The engineers who create the algorithms behind everything from autonomous vehicles to gene splicing equipment should also learn the art of ethical reasoning. It can be hard, though necessary, to consider current—and future—implications of today’s systems, she said.

“We aim to teach ethical reasoning skills that students will bring to their work from the design stage forward,” Simmons said. “It's not about conforming to fixed ethical ‘rules’ but learning how to reason in the space of values. There will always be conflicting values among the many stakeholders in the system being designed, such as users producers, the government, etc.”

Embedded EthiCS is comprised of modules “injected directly into existing core computer science courses,” Simmons said. The modules themselves result from collaboration between Harvard computer science and philosophy experts. The latter are primarily experts in ethical theory.

What about products beyond software? Some ethical considerations aren’t obvious at first blush. Philosophers, however, are already contemplating the ramifications of new technologies.

It was around 2012 when newspapers began printing stories on 3D-printed guns. Were they easy to make? Could just anyone print a gun at home?

The stories got Erica Neely, a philosophy professor at Ohio Northern University, thinking. The ethical considerations around 3D printing must go beyond guns, she reasoned. “I was interested in how 3D printing would affect more everyday things,” she said.

See Our Special Video Report: The Future of Engineering Workforce, Learning, and Skills

Intellectual property laws are one example.

“A lot of companies make their money selling spare parts. That’s the only way consumers can get those parts,” Neely said. “But if you can download a plan for the part and print it at home, those companies will go out of business.”

Is doing so unethical?

“It’s not really clear,” Neely said. “I can understand why those companies don’t want you to do that, but does intellectual property cover something as basic as the screws and fasteners these companies are making?”

It’s not clear whether items like the screws and fasteners merit IP protection, Neely said.

“It’s not something unique enough to really deserve protection. You can’t really trademark things like that,” Neely said. “But it’s something we didn’t really have to think about until now.”

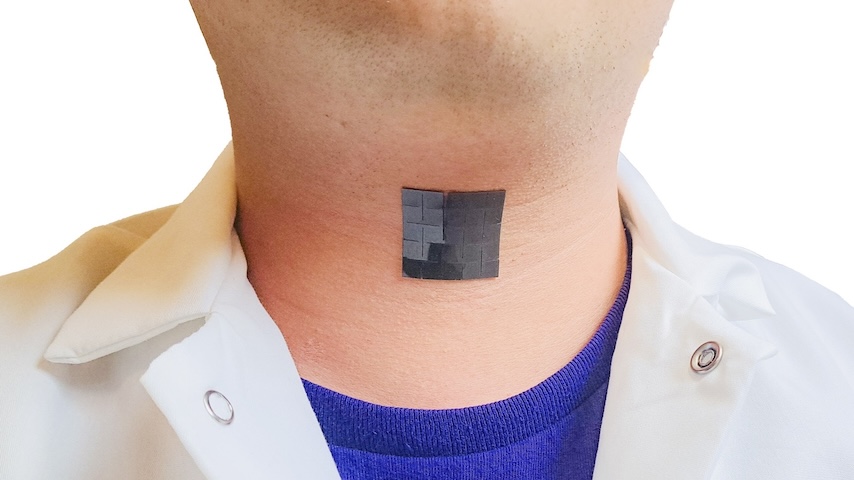

Another big debate centers on biomedical uses of 3D printers. While printers are expected to one-day create human organs for transplant, such as hearts and kidneys, they currently can be used to print simple items like the valves on oxygen ventilators.

Editor’s Pick: 7 Ways to Promote Professional Development in Your Remote Workforce

The problem is, the quality of the printed object varies, even among objects printed on the same model printer, at the same time, using the same material, Neely said.

“The [Food and Drug Administration] is really interested in this problem. Because obviously if you’re making ventilator valves you don’t want them to be OK on one printer but not so great on the other. We want this to be safe all the way through,” she said.

In 2016, the FDA released a draft document concerning the technical considerations of additive manufacturing. The document made recommendations for best practices, though the FDA has yet to release final rules on the matter.

And what of the future? Engineers and scientists working today will need to consider the ethical implications of work that won’t reach the market for many years.

For instance, scientists expect future medications to be customized to the consumer and then 3D printed. If needed your medication to kick in at lunchtime, be reduced around 5 p.m., and then increased around 9 p.m., your personalized pill could take care of that.

But customized medicine would also need to be regulated, Neely pointed out. And Many of the lauded uses for 3D printing also come with a flip side.

“The flip side of printing chemicals is the possibility of printing biological weapons,” she said. “I would sure like us not to do that, but if you can print chemicals that help people you can print chemicals that don’t.”

The future isn’t certain. The technologies being worked on today could all come with a flip side, or many flip sides, of which we can’t yet conceive.

That underscores the reason engineers and scientists need to be grounded in ethical reasoning, Simmons said. Engineers and philosophers aren’t so far apart after all.

Jean Thilmany is an engineering and technology writer based in Saint Paul, Minn.

The need for ethical reasoning is greater than ever, said James Mickens, who co-directs of the Embedded EthiCS program at Harvard University. For example, autonomous cars free humans from driving, but may pose new risks to drivers and pedestrians. Facial recognition systems speed lines but can discriminate against certain populations.

Today’s computer scientists must learn to design systems that are morally and socially responsible, said Alison Simmons, a Harvard philosophy professor. Engineers are no different.

More for You: Workforce Blog: Opening Doors to Opportunity

Computer science majors at Harvard now study ethics through Embedded EthiCS modules. The program teaches students how to think through the ethical implications of their work, she said. Simmons also co-directs program.

The engineers who create the algorithms behind everything from autonomous vehicles to gene splicing equipment should also learn the art of ethical reasoning. It can be hard, though necessary, to consider current—and future—implications of today’s systems, she said.

“We aim to teach ethical reasoning skills that students will bring to their work from the design stage forward,” Simmons said. “It's not about conforming to fixed ethical ‘rules’ but learning how to reason in the space of values. There will always be conflicting values among the many stakeholders in the system being designed, such as users producers, the government, etc.”

Embedded EthiCS is comprised of modules “injected directly into existing core computer science courses,” Simmons said. The modules themselves result from collaboration between Harvard computer science and philosophy experts. The latter are primarily experts in ethical theory.

Principled 3D Printing

What about products beyond software? Some ethical considerations aren’t obvious at first blush. Philosophers, however, are already contemplating the ramifications of new technologies.

It was around 2012 when newspapers began printing stories on 3D-printed guns. Were they easy to make? Could just anyone print a gun at home?

The stories got Erica Neely, a philosophy professor at Ohio Northern University, thinking. The ethical considerations around 3D printing must go beyond guns, she reasoned. “I was interested in how 3D printing would affect more everyday things,” she said.

See Our Special Video Report: The Future of Engineering Workforce, Learning, and Skills

Intellectual property laws are one example.

“A lot of companies make their money selling spare parts. That’s the only way consumers can get those parts,” Neely said. “But if you can download a plan for the part and print it at home, those companies will go out of business.”

Is doing so unethical?

“It’s not really clear,” Neely said. “I can understand why those companies don’t want you to do that, but does intellectual property cover something as basic as the screws and fasteners these companies are making?”

It’s not clear whether items like the screws and fasteners merit IP protection, Neely said.

“It’s not something unique enough to really deserve protection. You can’t really trademark things like that,” Neely said. “But it’s something we didn’t really have to think about until now.”

Another big debate centers on biomedical uses of 3D printers. While printers are expected to one-day create human organs for transplant, such as hearts and kidneys, they currently can be used to print simple items like the valves on oxygen ventilators.

Editor’s Pick: 7 Ways to Promote Professional Development in Your Remote Workforce

The problem is, the quality of the printed object varies, even among objects printed on the same model printer, at the same time, using the same material, Neely said.

“The [Food and Drug Administration] is really interested in this problem. Because obviously if you’re making ventilator valves you don’t want them to be OK on one printer but not so great on the other. We want this to be safe all the way through,” she said.

In 2016, the FDA released a draft document concerning the technical considerations of additive manufacturing. The document made recommendations for best practices, though the FDA has yet to release final rules on the matter.

And what of the future? Engineers and scientists working today will need to consider the ethical implications of work that won’t reach the market for many years.

For instance, scientists expect future medications to be customized to the consumer and then 3D printed. If needed your medication to kick in at lunchtime, be reduced around 5 p.m., and then increased around 9 p.m., your personalized pill could take care of that.

But customized medicine would also need to be regulated, Neely pointed out. And Many of the lauded uses for 3D printing also come with a flip side.

“The flip side of printing chemicals is the possibility of printing biological weapons,” she said. “I would sure like us not to do that, but if you can print chemicals that help people you can print chemicals that don’t.”

The future isn’t certain. The technologies being worked on today could all come with a flip side, or many flip sides, of which we can’t yet conceive.

That underscores the reason engineers and scientists need to be grounded in ethical reasoning, Simmons said. Engineers and philosophers aren’t so far apart after all.

Jean Thilmany is an engineering and technology writer based in Saint Paul, Minn.