An Autonomous Blood Test

An Autonomous Blood Test

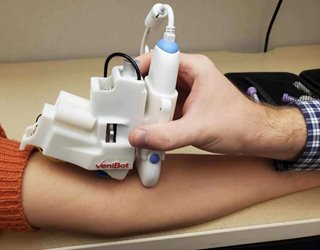

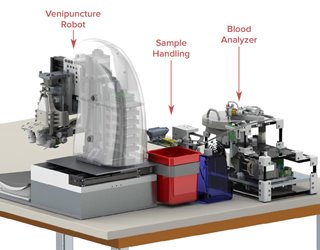

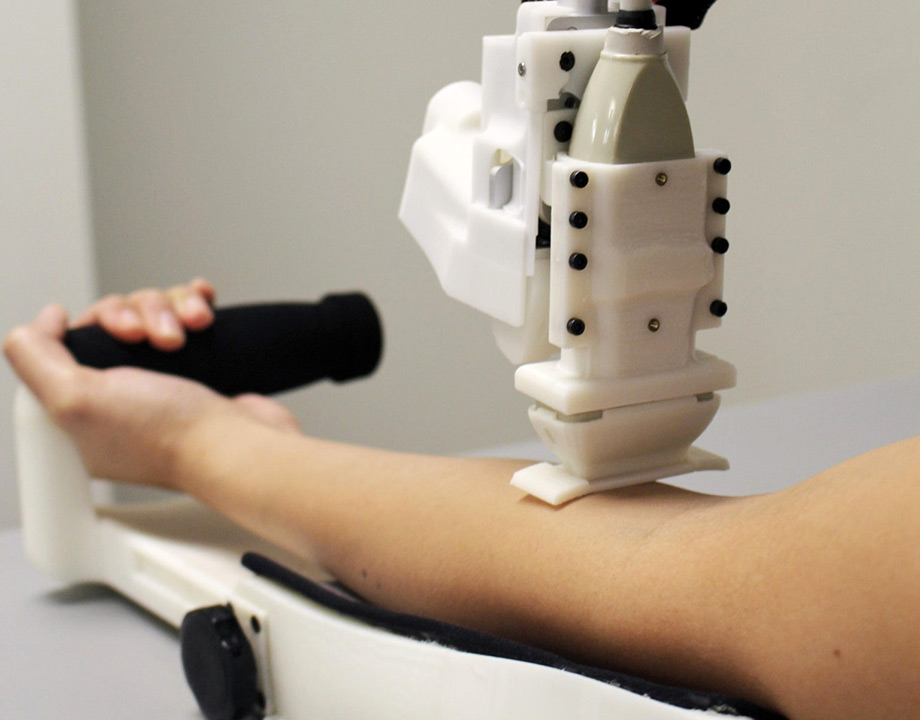

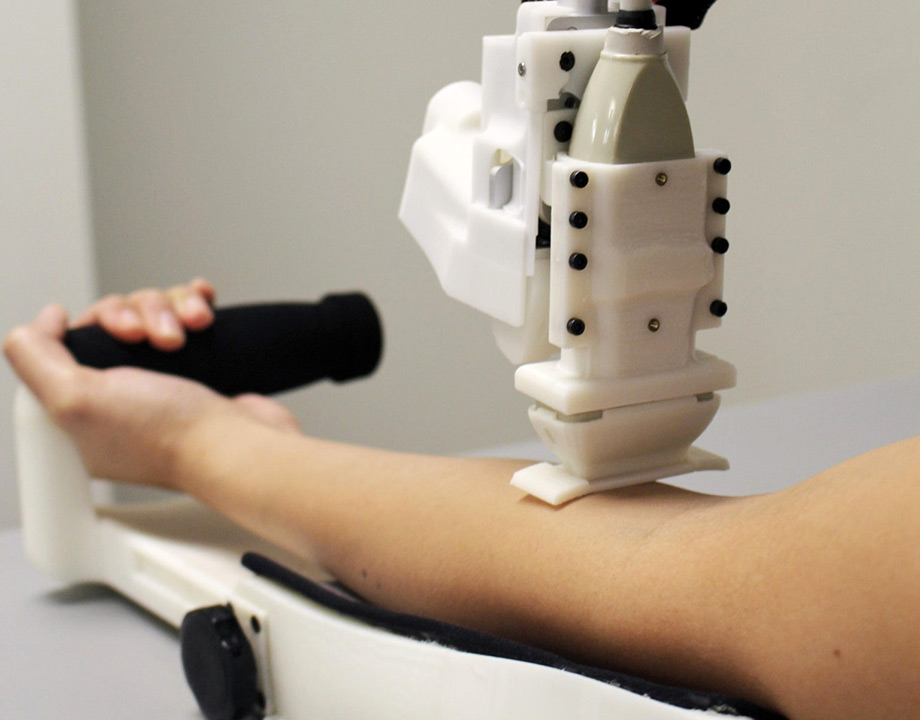

Prototype of the automated blood drawing and testing device developed at Rutgers University. Image: Unnati Chauhan, Rutgers University

The blood test is an ubiquitous tool of medicine—billions of them are done each year in the U.S. alone—as is the IV line. Both require a needle to find a vein. But as anyone who has endured more than one stab of the needle when giving a blood sample knows, the task is not always so easy. For patients with veins that aren’t visible on the surface, medical practitioners fail to find one 27 percent of the time. For emaciated patients the failure rate shoots up to 60 percent.

For better accuracy, it might be time to turn the job over to the robots. Researchers at Rutgers University have created just such a blood-tapping machine. It’s now been tested on human patients, and it outperforms human practitioners.

The Venibot, as it’s called, owes its venipuncture precision to ultrasound. The tried and true imaging technology allows the robot to identify an appropriate target vessel and then align the needle with it. “Then, just before the insertion, it will signal with an LED light,” said Josh Leipheimer, a biomedical engineering doctoral student at the university, who lead the research. After the warning, the needles goes in, guided continuously by the ultrasound.

Learn more about The Blood Test Goes Mobile

The team that Leipheimer worked with had previously produced a fully automated desktop version (not yet tested in vivo). But Leipheimer felt a more portable device was needed. For one thing, it was important to reach patients that might not be able to travel to a stationary device, whether they were bed-ridden in a hospital, at home, or in an ambulance. But it was also important to give patients—at least 10 percent to 20 percent of whom suffer from trypanophobia, a fear of needles or medical procedures—“that human factor and human-supervised component,” said Leipheimer. “I consider this to be a human-supervised or semi-automated, device. It’s still held by human operators over the general insertion area—the device takes care of the rest.”

The robot’s software compensates for any small movements on the part of the patient and of the blood bot doesn’t find a suitable vessel, it won’t attempt to insert. But finding the right vessel is only one challenge for medical practitioners taking blood or installing an IV line. Another is vessel rolling, where a vein moves away from the needle at contact. Leipheimer’s newest prototype will eliminate the problem with additional degrees of freedom and machine learning algorithms that take in data from previous attempts. “Then it can better optimize its insertion parameters for a stick success,” said Leipheimer.

The primary challenge he faced was combining the ultrasound with needle manipulation. “You’re attempting to use the data from the ultrasound—this vessel position—to determine the necessary movements from the needle to reach this point,” he added.

That software is built on machine learning, but its behavior is not an impenetrable black box. “It’s possible to get a glimpse of what the machine learning model is doing,” said Leipheimer. “You can see it’s looking for certain features that are characteristic of a vessel: circular regions, dark patches—it puts all that together.”

Editor's Pick: The Robot Will See You Now

Phlebotomists of the world probably don’t have to start looking for a new job. “My intention is not to end the traditional manual approach,” said Leipheimer. “The goal is having something like this for those difficult situations where the vessel is not visible.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, N.J.

For better accuracy, it might be time to turn the job over to the robots. Researchers at Rutgers University have created just such a blood-tapping machine. It’s now been tested on human patients, and it outperforms human practitioners.

The Venibot, as it’s called, owes its venipuncture precision to ultrasound. The tried and true imaging technology allows the robot to identify an appropriate target vessel and then align the needle with it. “Then, just before the insertion, it will signal with an LED light,” said Josh Leipheimer, a biomedical engineering doctoral student at the university, who lead the research. After the warning, the needles goes in, guided continuously by the ultrasound.

Learn more about The Blood Test Goes Mobile

The team that Leipheimer worked with had previously produced a fully automated desktop version (not yet tested in vivo). But Leipheimer felt a more portable device was needed. For one thing, it was important to reach patients that might not be able to travel to a stationary device, whether they were bed-ridden in a hospital, at home, or in an ambulance. But it was also important to give patients—at least 10 percent to 20 percent of whom suffer from trypanophobia, a fear of needles or medical procedures—“that human factor and human-supervised component,” said Leipheimer. “I consider this to be a human-supervised or semi-automated, device. It’s still held by human operators over the general insertion area—the device takes care of the rest.”

The robot’s software compensates for any small movements on the part of the patient and of the blood bot doesn’t find a suitable vessel, it won’t attempt to insert. But finding the right vessel is only one challenge for medical practitioners taking blood or installing an IV line. Another is vessel rolling, where a vein moves away from the needle at contact. Leipheimer’s newest prototype will eliminate the problem with additional degrees of freedom and machine learning algorithms that take in data from previous attempts. “Then it can better optimize its insertion parameters for a stick success,” said Leipheimer.

The primary challenge he faced was combining the ultrasound with needle manipulation. “You’re attempting to use the data from the ultrasound—this vessel position—to determine the necessary movements from the needle to reach this point,” he added.

That software is built on machine learning, but its behavior is not an impenetrable black box. “It’s possible to get a glimpse of what the machine learning model is doing,” said Leipheimer. “You can see it’s looking for certain features that are characteristic of a vessel: circular regions, dark patches—it puts all that together.”

Editor's Pick: The Robot Will See You Now

Phlebotomists of the world probably don’t have to start looking for a new job. “My intention is not to end the traditional manual approach,” said Leipheimer. “The goal is having something like this for those difficult situations where the vessel is not visible.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer based in Westfield, N.J.