10 Smart Startups

10 Smart Startups

Superstar Cities are known for their technology startups, but innovative companies are popping up all over the United States.

When you think of the word “startups” it’s hard not to tack “Silicon Valley” to the front. Ever since Bill Hewlett and David Packard began their electronics company in a Palo Alto garage in 1938, that slice of northern California has been a global innovation hub. Thanks to the concentration of small technology companies that grew into gargantuan corporations, an independent California would have the fifth largest gross domestic product in the world, surpassed only by Germany, Japan, China, and the remainder of the United States.

The wealth of Silicon Valley has also spawned venture capital firms looking to invest in the next Apple or Google, but much of their search is limited to entrepreneurs in a few cities. In fact, a December 2019 report by the Brookings Institution found that 90 percent of the nation’s innovation sector employment growth in the last 15 years was generated in just five major coastal cities: Seattle, Boston, San Francisco, San Diego, and San Jose, Calif. These so-called Superstar Cities, plus New York City and Washington, D.C., have engaged in what writer Richard Florida termed “winner-take-all urbanism,” attracting more than their share of capital and talented young people. The rest of the country, in this view, was being left behind.

But focusing only on Superstar Cities means missing out on some of the most interesting young companies around. To show the diversity of innovation outside the so-called innovation hubs, we are spotlighting 10 startups or young companies developing products in a variety of engineering fields. Some of these companies are located in small towns, others in large cities not necessarily known for their entrepreneurship. Some are tapping into local universities or resources; almost all are in cities that can offer a high quality of life at an affordable cost.

In recent months as many professionals have acclimated to working from home due to the coronavirus pandemic, some have wondered whether Superstar Cities might lose their luster. If you can work from home, why does that home have to be in Cambridge, Mass., or San Jose, Calif.? As this selection of smart young companies shows, people are already innovating in far-flung places.

What do you get when you combine data and dogs? Perhaps a Fitbit for Fido.

Davide Rossi is an engineer who was using a monitor to track his daily activity when he realized that there was a user base that wasn’t being tapped. “Animals cannot tell us how they are doing and when they’re getting sick,” Rossi said. “Our ‘big idea’ was really to start gathering real-time, comparative, cloud-based behavioral insights into dog health and location, and use those insights to be better pet parents.”

Together with Sara Rossi and Fabrizio Filippini, Rossi founded FitBark as a platform for collecting and presenting health data for pets. Collar sensors collect data on a pet’s location, activity, quality of sleep, calorie balance, anxiety, skin conditions, and more. Rossi calls FitBark “a health and motivational platform for both pets and their owners,” since there’s evidence that people will be more active than they normally would if it’s part of a program to provide their pets more exercise.

Editors' Pick: Top 10 Growing Smart Cities

Rossi started the company in New York, but came to Kansas City as part of a mobile health accelerator program and discovered the smaller city was a perfect fit. “Quality of life, cost of living, and cost of hiring are up on the list,” Rossi said. “But the hidden gem here is the Animal Health Corridor, an ecosystem of more than 300 animal health companies that collectively account for over half of the global sales in animal pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and food. Being a part of this ecosystem has been invaluable.”

Some places are easy to implement Internet of Things solutions; oil and gas fields are something else altogether. Matt Harrison, CEO of WellAware, listed the challenges: “Very remote and hazardous operating conditions, the need to solve for last mile connectivity challenges, and a great diversity of ‘things’ to monitor and control—from pressure sensors to multimillion-dollar compressors and everything in between.”

Harrison, together with Cameron Powell, Gene Powell, and Trey Moore, founded WellAware, an infrastructure data company in San Antonio, to help oil and gas companies gain visibility into their critical assets. Rather than sending all data to a central cloud-computing facility for processing, the company focuses on the edge, close to the assets being monitored.

Because of that, the company says, its IoT systems are more robust and are more capable of transmitting high-quality and high-fidelity data to customers.

“Solving for the challenges in the oil and gas market has positioned WellAware ideally to rapidly expand into other industrial markets like manufacturing, logistics, utilities, defense, and many more.”

Locating the company in San Antonio wasn’t a problem, Harrison said. “Capital sources are still disproportionately established on the coasts. That said, if you have a compelling company and value proposition, you can always attract the right capital,” he said, adding, “This is an incredible place to live and work and play and it is the people—and the food—that make it that way.”

Many advanced manufacturing applications produce relatively small parts that are tucked away in the insides of larger machines. By contrast, the pieces printed by Branch Technology, a specialty manufacturer in Chattanooga, are hard to miss.

Branch was founded by Platt Boyd, an architect who was looking for a way to build advanced structures on an ordinary budget.

“Architects design these amazing, efficient, dynamic, impactful buildings, and unfortunately, the construction industry continues to struggle in building them,” said John McCabe, director of brand and communications at Branch. “It’s costly because it requires a lot of waste to create those big sexy curvilinear signature buildings. Only the starchitects get access to that level of budget.”

Platt realized that 3D printing could produce custom-built architectural parts, quickly and without the waste that comes from conventional construction processes. For instance, McCabe said, dimensional lumber such as two-by-fours are almost never used without cutting for length or angle. A 3D-printed part can be manufactured to the exact specifications needed. Branch Technology does that by means of large-scale robotic arms that maneuver print heads through large volumes. Unlike a lot of construction materials that are finished on-site, the fabricated pieces are completed in the Branch manufacturing plant and shipped to the construction site for assembly.

McCabe said that locating in Chattanooga offered a lot of advantages, from a proximity to federal research centers in Huntsville, Ala., and Oak Ridge, Tenn., to the city-wide fiber-optic network boasting download speeds of 10 Gb per second. “A majority of our employees are from California and New York,” McCabe said. “People are beginning to realize that you don’t have to live in those cities anymore to work for an innovative company.”

Aeronautical engineer Nicholas Guida was plane spotting out the window at the Seattle airport with his wife, when he realized the winglets so common today on the tips of aircraft create challenges under certain conditions. Guida had been working on modifications to passive winglets, but realized that the ability to essentially turn the winglets on and off would provide all the benefits without the downsides.

That insight prompted Guida to launch Tamarack Aerospace to design and build active winglets that would intelligently respond to flight conditions. Today, he serves as the CEO and the company now holds more than 30 patents on the technology.

Winglets on aircraft wings provide the advantage of a greater aspect ratio—the comparison of wingspan to wing depth—without the ungainliness of overly long wings. Tamarack’s design allows for the winglets to aerodynamically “turn off” in specific conditions, thus dumping additional loads that might otherwise require a more reinforced wing and the resulting additional weight.

According to the company, active winglets reduce fuel usage by up to one-third and provide smoother, safer flights. While the company has installed the technology on more than 100 Cesna jets, its winglets are compatible with virtually every kind of aircraft, both commercial and military. And the fuel savings are great enough to pay for the winglets to pay for themselves in as little as 16 months.

You May Also Like: 10 Innovative Engineering Institutes

Tamarack is headquartered in Sandpoint, a city of less than 10,000 in far northern Idaho. The company boasts the location is an advantage: Not only is it an aviation-friendly area, a Tamarack representative writes, but “Flying through Sandpoint’s spectacular landscapes is an added bonus.”

Completely solar-powered vehicles may be beyond our capabilities, but a small company from Rhode Island has found the next best thing. Warwick-based eNow designs and markets a system that uses solar panels on the top of a semi-tractor trailer to run refrigeration units, electric auxiliary power units, and more.

According to Guy C. Shaffer, eNow’s chief marketing officer, the conventional diesel-powered trailer refrigeration business is dominated by two large companies, neither of which has experience with solar power. “In 2017, we began applying our experience in helping to power heavy-duty trucks to develop an all-electric truck refrigeration system using eNow solar systems and a Li-ion battery as the power source.”

CEO Jeff Flath had developed the first, wholly solar-powered “eco” billboard in Times Square for Ricoh America. He realized that solar panels could be used to power auxiliary systems on trucks and buses. Tests in California during the summer have shown that the system can keep produce refrigerated at a cool 36 °F for up to 12 hours. The company has partnered with Wabash National trailer company to market a refrigerated trailer which promises reduced operating costs as well as a smaller environmental impact.

“Rhode Island may be small,” Shaffer said, “but it has exceptional schools, arts, history, culture, restaurants—and as the Ocean State—beaches, boating, and fishing. Why leave?”

“We’re going to be using diesel engines for a long time,” said Tom Waldron, executive vice president at SuperTurbo Technologies, “so it’s important to make them as clean and efficient as possible.” That’s the philosophy behind the Loveland, Colo.-based company, which is developing a fully mechanical driven turbocharger that provides the benefits of supercharging, turbocharging, and turbo-compounding in one device.

The turbocharger includes a planetary traction drive that enables power transfer to and from the turbo shaft. The drive utilizes smooth rollers that transmit torque through a special traction fluid. Because the power is transferred this way rather than via direct contact of gear teeth, it can operate at speeds in excess of 100,000 rpm. The company says its device could provide fuel savings of up to 10 percent for a large diesel-powered truck.

Driven turbochargers provide the ability to precisely control and balance boost pressure and air fuel ratio. The controls can be used to optimize fuel efficiency and emissions at different operating points. The device is designed to be integrated with the engines of large trucks without modifications.

“We’re not asking anyone to change their vehicle architecture,” Waldron said, who added that the technology is at technological readiness level 7—a couple steps from production.

The company was spun off from Woodward Governor and stayed in north-central Colorado to take advantage of its proximity to Colorado State University’s strong engineering program. According to Waldron, “Our engineer retention is enhanced by the high quality of life in Northern Colorado.”

Keeping a steady view of a potential target is critically important for military systems. But that’s hard to do when the target is a small unmanned aerial vehicle. Creating multispectral vision systems capable of detecting, locating, tracking, and identifying UAVs—all while mounted on the roof of a ground vehicle travelling at 40 mph—is the specialty of Ascent Vision Technologies.

The company builds gyro-stabilized imaging systems and fully integrated solutions for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions for armed forces and security groups all over the world. In addition to finding UAVs, the company’s X-MADIS anti-drone system features an electronic warfare capability to knock the target out of the sky.

AVT started as a provider of aerial firefighting surveillance technologies. The imaging systems that were developed for spotting and monitoring forest fires quickly found national security applications.

Pork is a huge industry in the Midwest, but raising hogs is fraught with challenges. One of the biggest unfolds in the first days after a piglet is born: Piglets need to be kept warm, but the traditional method farmers use—a heat lamp in the farrowing crate—is inefficient and helps only the one or two piglets directly under the light. (Chilly piglets often try to nestle under their mothers and risk getting crushed.)

Amos Petersen co-founded FarrPro just months after graduating from the University of Iowa with degrees in engineering and economics, and quickly introduced the company’s first product, the Haven. The big idea behind the Haven was to place a long heating element inside a parabolic reflector, creating a much larger and more sheltered area for piglets to stay warm.

What’s more, because the reflector better concentrates the heat, not only does it allow sows to keep cooler—they prefer temperatures that are 20 °F cooler than what piglets need—but the efficient heating element also cuts energy use nearly in half.

It’s not just a neat-sounding idea—farmers have quickly seen its value. The company has sold more than 300 units to farmers around the Midwest, and the Haven was recognized by National Hog Farmer with its Producers’ Choice Award in 2019 and received the Aherne Prize for Innovative Pork Production, bestowed by Canadian pork producers, in 2020.

Drones are great for getting a bird’s-eye view of a situation. But because of weight limitations, the batteries they can carry mean they can only stay aloft for an hour or so. What would really help would be to attach an extension cord to run the drone’s electric motors.

That sounds a bit smart-aleck-y but that’s essentially what Hoverfly Technologies, a company in Orlando, has produced. Since the power supply is on the ground and sent up a 200-foot cable, the tethered drone system can stay aloft almost indefinitely. The New York City Fire Department has deployed one of Hoverfly’s tethered drones to monitor the roof of a building before firefighters attempted to access it.

Recommended for You: 10 Influential Women in Engineering

Founded by Daniel Burroughs and Alfred Ducharme, two faculty members at the University of Central Florida, the company has been focusing on large institutional users: defense, security, public safety, and owners of critical infrastructure.

One version, sporting high-definition cameras and a communications cable running to a golf cart, has been developed for use at sporting events.

The company markets its drones as capable of flying autonomously, and they can be equipped with specialty instruments such as infrared cameras and communication detectors.

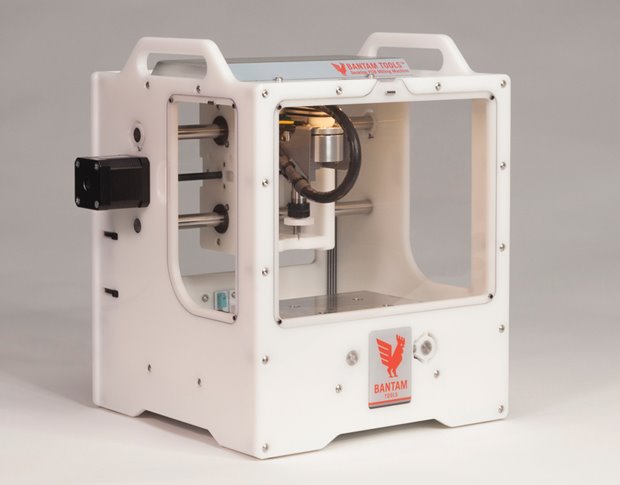

The Bantam Tools CNC mill looks for all the world like a desktop 3D printer, but it works in almost the exact opposite way: It takes a larger slab of material and gradually removes bits to produce something useful. The spindle turns at such a high speed—up to 26,000 rpm—that the mill can not only cut wood and plastic as can many laser cutters, but also carve into aluminum and brass. That makes it useful for machining small parts that can go right into a product.

The company was founded as Othermill by Danielle Applestone to enable individuals and small companies access to the power of machining tools at a fraction of the cost. It was purchased in 2017 by Bre Pettis, who had success in democratizing 3D printing through his MakerBot, which he had sold to Stratasys in 2013. Together, Applestone and Pettis decided to relocate the small company to Peekskill, N.Y., a former industrial town on the Hudson River.

One of the main advantages was cost: For what the company had been paying for rent in the Bay Area, it could afford to buy an entire 8,700 square-foot industrial building that had been sitting vacant for years. And the cost of housing was considerably lower.

The desktop mill is marketed as a means for producing printed circuit boards, in which wires are replaced by conductive etchings. But makers—the hardware hobbyists who took to Pettis’s MakerBot—are finding creative ways to use the mill for crafts and home projects.

Jeffrey Winters is Editor-in-Chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

The wealth of Silicon Valley has also spawned venture capital firms looking to invest in the next Apple or Google, but much of their search is limited to entrepreneurs in a few cities. In fact, a December 2019 report by the Brookings Institution found that 90 percent of the nation’s innovation sector employment growth in the last 15 years was generated in just five major coastal cities: Seattle, Boston, San Francisco, San Diego, and San Jose, Calif. These so-called Superstar Cities, plus New York City and Washington, D.C., have engaged in what writer Richard Florida termed “winner-take-all urbanism,” attracting more than their share of capital and talented young people. The rest of the country, in this view, was being left behind.

But focusing only on Superstar Cities means missing out on some of the most interesting young companies around. To show the diversity of innovation outside the so-called innovation hubs, we are spotlighting 10 startups or young companies developing products in a variety of engineering fields. Some of these companies are located in small towns, others in large cities not necessarily known for their entrepreneurship. Some are tapping into local universities or resources; almost all are in cities that can offer a high quality of life at an affordable cost.

In recent months as many professionals have acclimated to working from home due to the coronavirus pandemic, some have wondered whether Superstar Cities might lose their luster. If you can work from home, why does that home have to be in Cambridge, Mass., or San Jose, Calif.? As this selection of smart young companies shows, people are already innovating in far-flung places.

FitBark, Kansas City, Mo.

What do you get when you combine data and dogs? Perhaps a Fitbit for Fido.

Davide Rossi is an engineer who was using a monitor to track his daily activity when he realized that there was a user base that wasn’t being tapped. “Animals cannot tell us how they are doing and when they’re getting sick,” Rossi said. “Our ‘big idea’ was really to start gathering real-time, comparative, cloud-based behavioral insights into dog health and location, and use those insights to be better pet parents.”

Together with Sara Rossi and Fabrizio Filippini, Rossi founded FitBark as a platform for collecting and presenting health data for pets. Collar sensors collect data on a pet’s location, activity, quality of sleep, calorie balance, anxiety, skin conditions, and more. Rossi calls FitBark “a health and motivational platform for both pets and their owners,” since there’s evidence that people will be more active than they normally would if it’s part of a program to provide their pets more exercise.

Editors' Pick: Top 10 Growing Smart Cities

Rossi started the company in New York, but came to Kansas City as part of a mobile health accelerator program and discovered the smaller city was a perfect fit. “Quality of life, cost of living, and cost of hiring are up on the list,” Rossi said. “But the hidden gem here is the Animal Health Corridor, an ecosystem of more than 300 animal health companies that collectively account for over half of the global sales in animal pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and food. Being a part of this ecosystem has been invaluable.”

WellAware, San Antonio, Tex.

Some places are easy to implement Internet of Things solutions; oil and gas fields are something else altogether. Matt Harrison, CEO of WellAware, listed the challenges: “Very remote and hazardous operating conditions, the need to solve for last mile connectivity challenges, and a great diversity of ‘things’ to monitor and control—from pressure sensors to multimillion-dollar compressors and everything in between.”

Harrison, together with Cameron Powell, Gene Powell, and Trey Moore, founded WellAware, an infrastructure data company in San Antonio, to help oil and gas companies gain visibility into their critical assets. Rather than sending all data to a central cloud-computing facility for processing, the company focuses on the edge, close to the assets being monitored.

Because of that, the company says, its IoT systems are more robust and are more capable of transmitting high-quality and high-fidelity data to customers.

“Solving for the challenges in the oil and gas market has positioned WellAware ideally to rapidly expand into other industrial markets like manufacturing, logistics, utilities, defense, and many more.”

Locating the company in San Antonio wasn’t a problem, Harrison said. “Capital sources are still disproportionately established on the coasts. That said, if you have a compelling company and value proposition, you can always attract the right capital,” he said, adding, “This is an incredible place to live and work and play and it is the people—and the food—that make it that way.”

Branch Technology, Chattanooga, Tenn.

Many advanced manufacturing applications produce relatively small parts that are tucked away in the insides of larger machines. By contrast, the pieces printed by Branch Technology, a specialty manufacturer in Chattanooga, are hard to miss.

Branch was founded by Platt Boyd, an architect who was looking for a way to build advanced structures on an ordinary budget.

“Architects design these amazing, efficient, dynamic, impactful buildings, and unfortunately, the construction industry continues to struggle in building them,” said John McCabe, director of brand and communications at Branch. “It’s costly because it requires a lot of waste to create those big sexy curvilinear signature buildings. Only the starchitects get access to that level of budget.”

Platt realized that 3D printing could produce custom-built architectural parts, quickly and without the waste that comes from conventional construction processes. For instance, McCabe said, dimensional lumber such as two-by-fours are almost never used without cutting for length or angle. A 3D-printed part can be manufactured to the exact specifications needed. Branch Technology does that by means of large-scale robotic arms that maneuver print heads through large volumes. Unlike a lot of construction materials that are finished on-site, the fabricated pieces are completed in the Branch manufacturing plant and shipped to the construction site for assembly.

McCabe said that locating in Chattanooga offered a lot of advantages, from a proximity to federal research centers in Huntsville, Ala., and Oak Ridge, Tenn., to the city-wide fiber-optic network boasting download speeds of 10 Gb per second. “A majority of our employees are from California and New York,” McCabe said. “People are beginning to realize that you don’t have to live in those cities anymore to work for an innovative company.”

Tamarack Aerospace, Sandpoint, Idaho

Aeronautical engineer Nicholas Guida was plane spotting out the window at the Seattle airport with his wife, when he realized the winglets so common today on the tips of aircraft create challenges under certain conditions. Guida had been working on modifications to passive winglets, but realized that the ability to essentially turn the winglets on and off would provide all the benefits without the downsides.

That insight prompted Guida to launch Tamarack Aerospace to design and build active winglets that would intelligently respond to flight conditions. Today, he serves as the CEO and the company now holds more than 30 patents on the technology.

Winglets on aircraft wings provide the advantage of a greater aspect ratio—the comparison of wingspan to wing depth—without the ungainliness of overly long wings. Tamarack’s design allows for the winglets to aerodynamically “turn off” in specific conditions, thus dumping additional loads that might otherwise require a more reinforced wing and the resulting additional weight.

According to the company, active winglets reduce fuel usage by up to one-third and provide smoother, safer flights. While the company has installed the technology on more than 100 Cesna jets, its winglets are compatible with virtually every kind of aircraft, both commercial and military. And the fuel savings are great enough to pay for the winglets to pay for themselves in as little as 16 months.

You May Also Like: 10 Innovative Engineering Institutes

Tamarack is headquartered in Sandpoint, a city of less than 10,000 in far northern Idaho. The company boasts the location is an advantage: Not only is it an aviation-friendly area, a Tamarack representative writes, but “Flying through Sandpoint’s spectacular landscapes is an added bonus.”

eNow, Warwick, R.I.

Completely solar-powered vehicles may be beyond our capabilities, but a small company from Rhode Island has found the next best thing. Warwick-based eNow designs and markets a system that uses solar panels on the top of a semi-tractor trailer to run refrigeration units, electric auxiliary power units, and more.

According to Guy C. Shaffer, eNow’s chief marketing officer, the conventional diesel-powered trailer refrigeration business is dominated by two large companies, neither of which has experience with solar power. “In 2017, we began applying our experience in helping to power heavy-duty trucks to develop an all-electric truck refrigeration system using eNow solar systems and a Li-ion battery as the power source.”

CEO Jeff Flath had developed the first, wholly solar-powered “eco” billboard in Times Square for Ricoh America. He realized that solar panels could be used to power auxiliary systems on trucks and buses. Tests in California during the summer have shown that the system can keep produce refrigerated at a cool 36 °F for up to 12 hours. The company has partnered with Wabash National trailer company to market a refrigerated trailer which promises reduced operating costs as well as a smaller environmental impact.

“Rhode Island may be small,” Shaffer said, “but it has exceptional schools, arts, history, culture, restaurants—and as the Ocean State—beaches, boating, and fishing. Why leave?”

SuperTurbo Technologies, Loveland, Colo.

“We’re going to be using diesel engines for a long time,” said Tom Waldron, executive vice president at SuperTurbo Technologies, “so it’s important to make them as clean and efficient as possible.” That’s the philosophy behind the Loveland, Colo.-based company, which is developing a fully mechanical driven turbocharger that provides the benefits of supercharging, turbocharging, and turbo-compounding in one device.

The turbocharger includes a planetary traction drive that enables power transfer to and from the turbo shaft. The drive utilizes smooth rollers that transmit torque through a special traction fluid. Because the power is transferred this way rather than via direct contact of gear teeth, it can operate at speeds in excess of 100,000 rpm. The company says its device could provide fuel savings of up to 10 percent for a large diesel-powered truck.

Driven turbochargers provide the ability to precisely control and balance boost pressure and air fuel ratio. The controls can be used to optimize fuel efficiency and emissions at different operating points. The device is designed to be integrated with the engines of large trucks without modifications.

“We’re not asking anyone to change their vehicle architecture,” Waldron said, who added that the technology is at technological readiness level 7—a couple steps from production.

The company was spun off from Woodward Governor and stayed in north-central Colorado to take advantage of its proximity to Colorado State University’s strong engineering program. According to Waldron, “Our engineer retention is enhanced by the high quality of life in Northern Colorado.”

Ascent Vision Systems, Bozeman, Mont.

Keeping a steady view of a potential target is critically important for military systems. But that’s hard to do when the target is a small unmanned aerial vehicle. Creating multispectral vision systems capable of detecting, locating, tracking, and identifying UAVs—all while mounted on the roof of a ground vehicle travelling at 40 mph—is the specialty of Ascent Vision Technologies.

The company builds gyro-stabilized imaging systems and fully integrated solutions for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions for armed forces and security groups all over the world. In addition to finding UAVs, the company’s X-MADIS anti-drone system features an electronic warfare capability to knock the target out of the sky.

AVT started as a provider of aerial firefighting surveillance technologies. The imaging systems that were developed for spotting and monitoring forest fires quickly found national security applications.

FarrPro, Iowa City, Iowa

Pork is a huge industry in the Midwest, but raising hogs is fraught with challenges. One of the biggest unfolds in the first days after a piglet is born: Piglets need to be kept warm, but the traditional method farmers use—a heat lamp in the farrowing crate—is inefficient and helps only the one or two piglets directly under the light. (Chilly piglets often try to nestle under their mothers and risk getting crushed.)

Amos Petersen co-founded FarrPro just months after graduating from the University of Iowa with degrees in engineering and economics, and quickly introduced the company’s first product, the Haven. The big idea behind the Haven was to place a long heating element inside a parabolic reflector, creating a much larger and more sheltered area for piglets to stay warm.

What’s more, because the reflector better concentrates the heat, not only does it allow sows to keep cooler—they prefer temperatures that are 20 °F cooler than what piglets need—but the efficient heating element also cuts energy use nearly in half.

It’s not just a neat-sounding idea—farmers have quickly seen its value. The company has sold more than 300 units to farmers around the Midwest, and the Haven was recognized by National Hog Farmer with its Producers’ Choice Award in 2019 and received the Aherne Prize for Innovative Pork Production, bestowed by Canadian pork producers, in 2020.

Hoverfly, Orlando, Fla.

Drones are great for getting a bird’s-eye view of a situation. But because of weight limitations, the batteries they can carry mean they can only stay aloft for an hour or so. What would really help would be to attach an extension cord to run the drone’s electric motors.

That sounds a bit smart-aleck-y but that’s essentially what Hoverfly Technologies, a company in Orlando, has produced. Since the power supply is on the ground and sent up a 200-foot cable, the tethered drone system can stay aloft almost indefinitely. The New York City Fire Department has deployed one of Hoverfly’s tethered drones to monitor the roof of a building before firefighters attempted to access it.

Recommended for You: 10 Influential Women in Engineering

Founded by Daniel Burroughs and Alfred Ducharme, two faculty members at the University of Central Florida, the company has been focusing on large institutional users: defense, security, public safety, and owners of critical infrastructure.

One version, sporting high-definition cameras and a communications cable running to a golf cart, has been developed for use at sporting events.

The company markets its drones as capable of flying autonomously, and they can be equipped with specialty instruments such as infrared cameras and communication detectors.

Bantam Tools, Peekskill, N.Y.

The Bantam Tools CNC mill looks for all the world like a desktop 3D printer, but it works in almost the exact opposite way: It takes a larger slab of material and gradually removes bits to produce something useful. The spindle turns at such a high speed—up to 26,000 rpm—that the mill can not only cut wood and plastic as can many laser cutters, but also carve into aluminum and brass. That makes it useful for machining small parts that can go right into a product.

The company was founded as Othermill by Danielle Applestone to enable individuals and small companies access to the power of machining tools at a fraction of the cost. It was purchased in 2017 by Bre Pettis, who had success in democratizing 3D printing through his MakerBot, which he had sold to Stratasys in 2013. Together, Applestone and Pettis decided to relocate the small company to Peekskill, N.Y., a former industrial town on the Hudson River.

One of the main advantages was cost: For what the company had been paying for rent in the Bay Area, it could afford to buy an entire 8,700 square-foot industrial building that had been sitting vacant for years. And the cost of housing was considerably lower.

The desktop mill is marketed as a means for producing printed circuit boards, in which wires are replaced by conductive etchings. But makers—the hardware hobbyists who took to Pettis’s MakerBot—are finding creative ways to use the mill for crafts and home projects.

Jeffrey Winters is Editor-in-Chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.