Petal Power Boosts Solar Cell Capacity

Petal Power Boosts Solar Cell Capacity

Both photovoltaics and plant photosynthesis absorb light and convert it into a different form of energy. Power conversion efficiency is greatly affected by incomplete absorption of the sunlight. To maximize conversion, it is important to capture as much of the sun's light spectrum as possible, including light from all incidence angles as the angle changes with the sun’s position. Plants—which have developed this remarkable capability through a long evolutionary process—can provide clues for how to broaden the absorption spectrum and incidence angle tolerance of future solar cells.

“Nature has evolved complex micro-structured and nano-structured surfaces on the leaves and petals of plants that are very efficient in harvesting incoming photons,” says Guillaume Gomard, a photonics researcher at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology’s Light Technology Institute in Germany. “As both solar cells and plants should be efficient sunlight collectors operating under various illuminations conditions, that is, under different angles of incidence, we thought solar cells might benefit from the naturally designed structures found on plants.”

To investigate this idea, a research team led by Gomard, including scientists from the Center for Solar Energy and Hydrogen Research, decided to study the optical and anti-reflection properties of the epidermal cells in different plant species. Their work showed that the epidermal cells of rose petals have especially good anti-reflection properties. When this cell structure was incorporated into an organic solar cell, it increased the cell’s power conversion efficiency by 12 percent for vertically incident light.

Why Rose Petals?

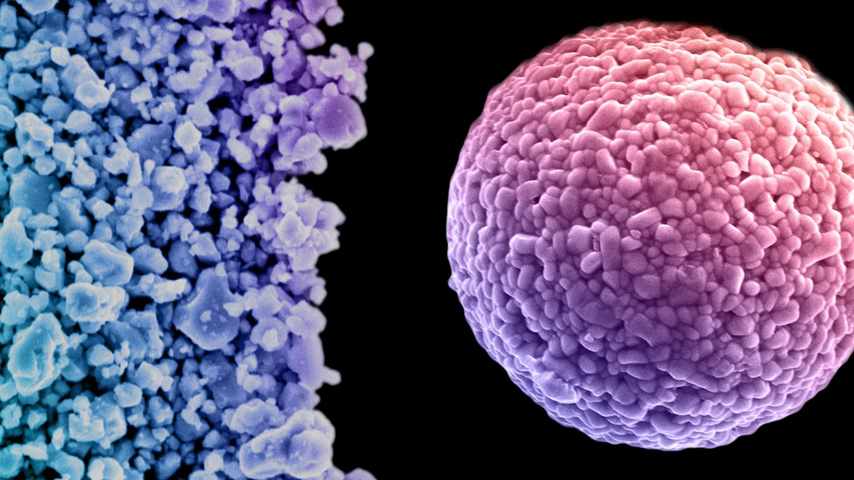

When Gomard and his fellow scientist investigated the optical and antireflection properties of different plant species, they focused especially on the antireflection effect of the epidermal cells. These properties are particularly pronounced in rose petals, where they provide stronger color contrasts and thus increase the chance of pollination. Using the electron microscope, “We discovered the epidermis of rose petals consists of a disorganized arrangement of densely packed microstructures, with additional ribs formed by randomly positioned nanostructures,” says Gomard.

To produce a synthetic replica of the structure, the team created a negative mold of the epidermis in a silicon-based polymer called polydimethylsiloxane, and then pressed this negative mold into transparent optical glue that was left to cure under UV light.

"This easy and cost-effective method creates microstructures of a depth and density that are hardly achievable with artificial techniques," adds Gomard.

The transparent replica of the rose petal epidermis was then integrated into an organic solar cell. This resulted in a power conversion efficiency gain of 12 percent for vertically incident light. At very shallow incidence angles, the efficiency gain was even higher. “This is primarily due to the excellent omnidirectional antireflection properties of the replicated epidermis that is able to reduce surface reflection to a value below five percent, even for a light incidence angle of nearly 80 degrees,” says Gomard. He also notes that each replicated epidermal cell works as a microlens that extends the optical path within the solar cell, enhancing the light-matter-interaction and increasing the probability that the photons will be absorbed.

Flower Power

Gomard’s research reveals that light-harvesting micro- and nano-hierarchical structures replicated from the epidermal cells of plantscan be exploited for photovoltaic applications when integrated into state-of-the-art organic solar cells. Their broadband and omnidirectional antireflection properties, combined with their light-trapping capability, result in significant conversion efficiency gains.

Particularly surprising to Gomard was the angular tolerance of the replicated structures. “If we take the example of reflection [integrated over the spectral range of interest, namely between 300–1,300 nm], it is just above five percent for an angle of incidence as high as 80 degrees,” he says. “In the same conditions, the reflection of a bare planar glass surface reaches more than 40 percent. Therefore, plant structures have very efficient omnidirectional optical properties and consequently are particularly well-suited to photovoltaic applications.”

This research leads to another basic question: What is the role of disorganization in complex photonic structures?

“Plant structures are disordered at many levels,” Gomard continues. “We are currently using optical simulations to analyze those structures and figure out if disorder has a significant impact on the overall optical properties. We believe this research area has great potential, not only for photovoltaic applications, but also designing anti-glaring films for buildings or self-cleaning surfaces with additional light-collecting properties.”

Mark Crawford is an independent writer.

Learn about the latest energy solutions at theASME Power & Energy Conference.

When integrated into an organic solar cell, the transparent replica of the rose petal epidermis resulted in a power conversion efficiency gain of 12 percent for vertically incident light.Guillaume Gomard, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology’s Light Technology Institute